Essaydi considers the ways in which women have been relegated to the private sphere:

Traditionally, the presence of men has defined public spaces: the streets, the meeting places, the places of work. Women, on the other hand, have been confined to private spaces, the architecture of the home. Physical thresholds define cultural ones, hidden hierarchies dictate patterns of habituation. Thus, crossing a permissible, cultural threshold into prohibited “space” in the metaphorical sense, can result in literal confinement in an actual space. . . . I am constraining the women within space and also confining them to their “proper” place, a place bounded by walls and controlled by men. The henna painted on their bodies corresponds to the elaborate pattern of the tiles. The women, then, become literal odalisques (odalisque, from the Turkish, means to belong to a place).1

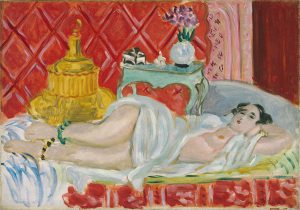

Essaydi’s photographs challenge the power of the male gaze to define and consume the female body as an object of desire. She calls upon the viewer to consider how stereotypes, often couched in beauty and adornment, actually serve to conceal and contain Arab women. Essaydi’s works also respond to canonical Western Orientalist paintings such as Eugène Delacroix’s Les Femmes d’Algiers (1834) and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ Grand Odalisque (1814) that present French fantasies of sexualized, indolent Arab women and life in the “Oriental” harem. Les Femmes du Maroc Revisited #1 is inscribed with a form of sacred calligraphy that women have been denied access to, literally rewriting the narrative around Arab women’s agency.

Eugène Delacroix, 1798–1863, France, Les Femmes d’Algiers dans leur appartement,

1834, Oil on canvas, The Louvre, Paris

1 Lalla Essaydi, “Artist Statement,” www.lallaessaydi.com.